How can a genre, a style of film so quintessential to the landscape of American cinema, one that stood as a cinematic landmark of its time, be nearly forgotten by the next century?

How did we so easily move on from one of the most influential chapters in film history and let it blow away into the dust?

When I first had the idea for this project, I felt like I was staring down the barrel of a gun. To everyone I asked, Westerns were the least interesting piece of film history I could explore.

“Why would you choose Westerns?”

“Like… old cowboy movies?”

“Oh, my dad used to watch those! I always thought they were sooo boring.”

That got me wondering: Why?

Why have we as a new generation of filmmakers and film lovers shunned such a vivid, mythic, and classically American genre?

Then it hit me. Just like Westerns have been pushed to the margins, so has much of the culture they represent. In America’s biggest cities, and in places like where I am from, country music, Southern dance, and rural traditions are often turned into parody and viewed with irony, if not outright dismissal.

So again -- Why?

The American Dream has always been tangled up with the idea of the West, striking gold, reinventing yourself, living on the edge of law and land. It was dirty and dangerous and often violent, but it was ours. As cities grew and tech took over, that nostalgic fantasy began to rust. Now, the fantasy that once captivated millions all feel like Hollywood phoniness. Cheap costumes and bad accents.

But I’m not convinced that’s all they are.

This project is my way of reclaiming curiosity, not just to expand my own knowledge of Westerns, but in my own small way to help crack open the conversation with more nuance, and with more respect.

So today, we dust off the bookshelves, pour ourselves a glass of our finest whiskey, and head back to where it all began:

The birth of the Western.

The genesis of the American Cowboy.

*~*~*~*

The legends that create the foundation for what a Western would be date far across time, but relatively the same place. Or the same idea of a place. The rise of cowboy pictures happens almost parallel to the rise of film itself.

The first moving picture ever made? A Black man on horseback. He rides more like an English gentleman than an outlaw but the image still holds striking connotations.

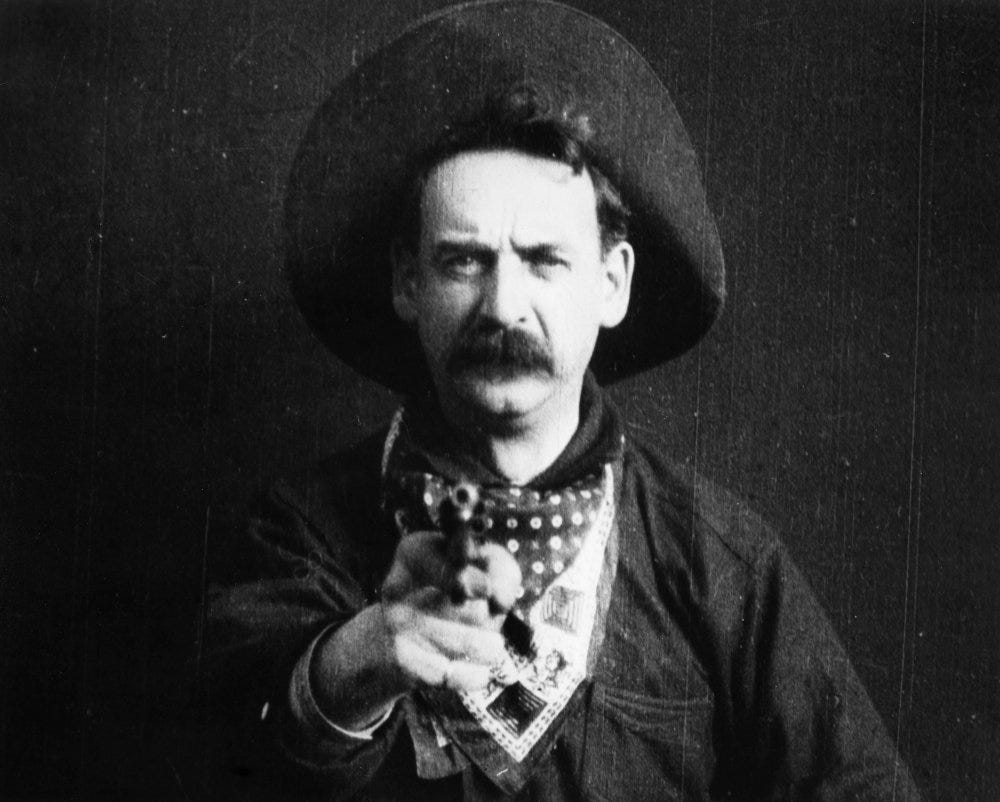

And of course there’s The Great Train Robbery (1903), the godfather of narrative film, and yes, a Western! This 12-minute short revolutionized cinema in ways so foundational, the art form might not exist without it.

Before The Great Train Robbery, most motion pictures were short, one-shot scenes of real life, like trains arriving or people walking, simple novelties of candid, everyday life. But this film introduced continuity editing and cross-cutting, which laid the groundwork for narrative storytelling in movies.

The director Edwin S. Porter used and effectively invited, cross-cutting to build suspense, camera movement (a pan during a chase scene was groundbreaking), hand-colored frames in some prints one of the early flirtations with color film. And in its infamous final shot the outlaw fired a pistol directly at the camera which shocked and terrified audiences.

It is often cited as the first "breaking the fourth wall" moment in film.

But even before that Western themes were created through popular 19th-century media that romanticized the frontier. Cheap dime novels and serials (1860s–1900s) turned the West into an adventure with a classic formula: a heroic frontier warrior (often an ex-soldier or scout), a vulnerable heroine, a ruthless outlaw gang, tense Indian encounters, and gunfights, with the fearless cowboy prevailing over chaos.

All of which are things that will continue to appear as classic tropes in films throughout this project.

Buffalo Bill Cody’s rise to fame was retold endlessly in dime novels, where he became “Buffalo Bill, the Buckskin King”, an educated soldier who still bests all rivals with sharpshooting skill.

As journals and newspapers spread across the Plains, frontier press accounts further shaped the myth. Regional papers from Dodge City, Deadwood and other cow towns eagerly reported cattle drives, range wars and shootouts.

At the same time, illustrated magazines published engravings of Indians, pioneers and battles, and photographers circulated iconic images of buffalo herds, rocky canyons and Native Americans. These visuals like Frederic Remington’s paintings of cavalry or stagecoach scenes gave concrete form to legends.

John Ford later admitted a 1907 Remington painting of a stagecoach raid inspired Stagecoach’s famous ambush.

Wild West shows and circus spectacles were perhaps the most direct forerunners of Western cinema. Buffalo Bill Cody’s touring Wild West extravaganza condensed frontier lore into theater: real cowboys, sharpshooters and Native performers dramatized buffalo hunts, mock battles and frontier life. These traveled all over the country, from small towns to the Chicago World's Fair in 1893.

These shows contrasted the “wild, primitive West” with the growing industrial East, transporting audiences to a “simpler time”.

Across all these media, certain themes recur: Manifest Destiny, individualism, frontier heroism and lawlessness. Writers of the time embraced the idea of continental expansion as predetermined. John L. O’Sullivan’s famous 1845 phrase spoke of the “manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence”. The lone cowboy epitomized this ideal.

At the same time, the frontier was portrayed as a savage no-man’s-land. Law enforcement was minimal, so stories celebrated vigilante justice and bloody standoffs. Yet heroes always prevailed. Frontier heroines and heroes (miners, scouts, or cavalrymen) embodied courage and moral strength, taming the wild by force or example. Buffalo Bill’s pitched battles and staged rescues, for instance, highlighted frontier heroism and sacrifice amid danger.

These pre-cinematic myths carried directly into early Western movies. In the silent era, filmmakers drew on familiar frontier narratives even as they experimented with the new medium.

As they did with the first film watched, both for this roundup, and this whole fine publication:

Hell’s Hinges (1916)

One of the first great feature film Westerns, exemplifies how 1910s films inherited the frontier mythos. Starring and co-directed by William S. Hart, this silent drama is set in a lawless Colorado town (“Hell’s Hinges”) that is described, go have “no Ten Commandments”, along with a saloon, a whorehouse and outlaw gangs.

When a preacher and his sister arrive to build a church, the town’s sin is exposed and chaotic violence follows. Hart’s character Blaze Tracy, a hard-drinking gunslinger, ultimately turns his fierce skill against the villains to save the redeemed community.

Notably, Hell’s Hinges subverts later Western optimism: the church is burned and many townsfolk die.

The film is soaked in overt Christian morality, redemption, damnation, and religious salvation are front and center. Later Westerns, especially mid-century ones, tend to deal more in shades of gray: ambiguous heroes, moral complexity, and critiques of civilization.

Many of the classic Western tropes weren’t structured yet. The town-taming gunslinger was still a new idea. There’s no horseback chase scene, no train robbery, no saloon standoff shot the way John Ford would later become known for.

I came to the realization that Hell’s Hinges was inventing the tropes, not following them. That makes it feel unfamiliar to people coming from a later viewership.

But as someone who has little experience with either Westerns, or Silent Films I was honestly a little jaded going into this. However I found myself being entertained throughout its relatively short runtime.

I thought the way it dealt with classic characters that predate any Western narrative, like a Preacher or a “Town Bully” and twisted them inside out was very clever. With the Preacher lacking the real ability to speak with or for God, and a hard blooded outlaw that is turned to light with the arrival of a good woman in town.

When I began watching this I was streaming through Tubi and one of the things that jumped out at me the most was the music. Which I thought was quite ironic.

“I am 30 minutes into this 65 minute movie and the only thing I can think about is how good the score is!!”

It was quite an interesting experience.

However around the same midway point I switched from watching the film on Tubi to watching on my phone on The Internet Archive.

And I noticed when I sat back down to start watching it that the score felt very… different.

It didn’t have the same grandiose, larger than life western score as it did when I was watching it before. This prompted me, once the film had finished, to do a little research into why I felt it sounded so different. Was it this part of the movie? Is it different from place to place? Did I just make this all up?

Turns out yes! and no.

I learned, through my research, that of course Silent Films were never really silent. They often had music and sound effects that, though not embedded, were essential to the viewing experience. However the silent film scores were never embedded within the film itself. It was played live, by a pianist, organist, or sometimes even a full orchestra, in the theater during the screening.

Some big releases came with cue sheets or suggested scores for theaters to follow, but smaller theaters often improvised.

So because the original films didn't have a locked-in score, every modern version you or I watch online will likely have a different musical accompaniment, chosen or composed by whoever restored or uploaded this particular version of the film.

But aside from the music and how I felt it affected the emotional tone of the second half of the movie I thought that Hell's Hinges was a very interesting and insightful film.

I felt like it had laid a stone for the genre that I didn’t quite understand yet.

Like this is the ghost in the machine, shaping the genre from backstage.

But ghosts cast long shadows.

Watching Hell’s Hinges felt like standing at the edge of a blueprint.

Like “Okay the pieces are there, rough-hewn and righteous, but they haven’t quite settled into what we now recognize as ‘a Western.’”

That but that recognition comes a little later.

With The Virginian (1929), the genre starts finding its voice. …Literally?

This was the first major sound Western, and it marks the genre’s slow shift from silent morality tale to cinematic mythmaking. It introduces us to a type we’ll see over and over again: the quiet cowboy with a code, the conflicted love interest, the showdown that defines a man.

However out of the three films we saddled this week, it was my least favorite.

I respected the way The Virginian handled the themes of the of law and justice, which is more complex than I expected. Especially in the questions it raises about the ambiguity of the death sentence.

The hanging scene, where the title character is forced to preside over the execution of his own friend, is handled with a somber gravity that feels ahead of its time. It’s not played for drama, but dread. The weight of that decision the burden of doing “what a man’s gotta do” becomes a recurring theme in Westerns, and The Virginian plants that seed early.

But for all that, the film didn’t quite stick with me emotionally. A lot of the pacing is slow and the performances feel like they’re still shaking off the stiffness of the silent era. The only moment that really lingered was a scene that seemed totally out of left field: the two main characters casually talking about Romeo and Juliet. It’s bizarrely tender and subtle in how it sets up both the blossoming romance and the two respective characters.

Still, it sets the table. And by the time we get to Stagecoach (1939), John Ford doesn’t just serve the meal, he carves the whole damn cow.

By and large John Ford is the Western director of all time. Guns drawn, hands down. He directed some of the most famous, and most genre-defining Westerns of all time, a lot of which we are going to watch in future weeks!!

But one of his most influential is Stagecoach.

Influential beyond just the Western genre. It is the only film this week that has permeated the public consciousness and had moments that I recognized from parodies, references, and influence on other films.

This was one of the first films to incorporate a more ensemble focused narrative into the genre. Historically, Westerns focused on a single character, usually a man, and the people that he met who in turn were usually one dimensional. But in Stagecoach Ford introduces us to a large cast of nine individuals that all have an impact on the story, and the other characters they are with.

Over the course of the film these nine characters travel across the west in the titular Stagecoach through dangerous Apache territory. Each passenger comes from a different background, and their personal stories, along with mounting external threats…

Aboard the Stagecoach is:

Ringo Kid, an escaped outlaw seeking revenge for his murdered family

Dallas, a kind and misunderstood prostitute who’s been cast out by the town

Doc Boone, a drunk doctor

Lucy Mallory, a pregnant officer’s wife

Hatfield, a gambler claiming to protect Lucy’s honor

Gatewood, a banker secretly embezzling money

Mr. Peacock, a meek whiskey salesman

Buck, the stagecoach driver

Curley, the U.S. marshal riding shotgun and escorting Ringo

The film climaxes with an Apache attack and Ringo’s decision to face his enemies in Lordsburg. His showdown with the Plummer brothers settles his past, and the film closes with a romantic but bittersweet resolution as he and Dallas ride off together.

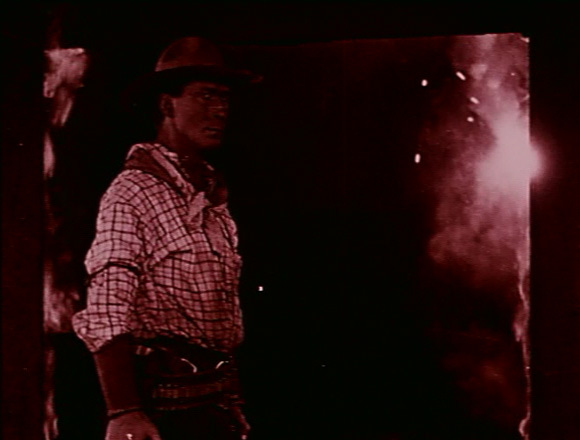

In one of the most iconic and exciting moments in the film John Wayne’s character jumps from horseback to horseback, in order to regain control of the Stagecoach while riding fast away from attacking Apache!

Dust is kicking up everywhere, the horses are running at top speed, Apache attackers are surrounding all of our characters inside the Stagecoach. It really is one of the most gripping and unique stunts I've ever seen put to film.

However, the film stumbles in a way that hobbles much of the genre: casual racism, particularly toward Native Americans.

The entire plot is driven by the fear of an Apache attack. This looming “savage” threat becomes the heartbeat of the film. While Stagecoach shifts its focus at times to interpersonal drama or class conflict, the Apache remain an off-screen menace until the climactic chase, where they appear more as obstacles than characters.

The racism here isn’t as overt as in some other Westerns, but that almost makes it worse; it’s in the erasure. The Apache are a faceless threat, a plot device, not people. Their humanity is never acknowledged, and that leaves a bitter aftertaste.

With Stagecoach, the Western finally finds its shape. But that shape will be bent, broken, and reimagined a hundred times over in the decades to come. Next week, we will ride deeper into the 1940s, 50s, and beyond.

What an amazing read. I love the origin story of you deciding on the topic, the explanation of how a score could and did change from theatre to theatre, the history of the genre, and how you discuss the common tropes and casual racism that existed during that time. I’m looking forward to learning much more on the topic.