Spaghetti Westerns: The Italian Revolution

Overture

Around the mid-1960s Italian filmmakers began to reimagine the Wild American Frontier, with films often being much grittier and more grim than the Westerns created in American Hollywood. These films, which have since been termed “Spaghetti Westerns” gave us some of the genre's most iconic and memorable moments and cliches. From the stone-faced no-name outlaw, to much more violent, bloody standoffs it all comes from here.

It’s fascinating that some of the most acclaimed and influential Westerns, a genre rooted in Americana, came from outsiders looking in. Two of the three films I watched this week are consistently cracking the Top 10 Westerns of All Time lists all over the place, and the other created a character, a name, or persona that was reimagined years later by one of the greatest contemporary directors: Quentin Tarantino.

It teeters on unbelievable, paradoxical even, that this should be the case. And I was well aware of this anomaly going into this week's films.

And yet, once again, I found that there always lies truth somewhere deeper than expected.

And much like searching for Confederate gold the real treasure doesn’t lie exactly where the map says…

But where did this specific sect of the genre come from?

Why did the Italians take a specific liking to the Western genre?

What leads them to be crowned as victors within the class?

Well, the end of World War II led Italian (and sometimes Spanish/German) filmmakers to make Westerns for their expressive potential, especially in the States, and their ability to shoot low-budget films in Spain’s Almería. That, in many ways, mimicked the American West.

Of course the genre surged: roughly 600 European Westerns were made between 1960–78. Nearly 500 of which were created in Italy alone. A staggering number considering films like Stagecoach had only really turned the conversation around Westerns away from Saturday matinee kid shows to serious adult cinema around two decades earlier.

And judging from what emerged out of the Spaghetti revolution, we can tell that these films were not aiming for an adolescent audience.

Spaghetti Westerns were born from constraint, over budget, space, and style but those very limits became the key to the genre’s global breakthrough.

What I have come across through much of my research, both firsthand watching the films, and secondhand reading articles and editorials, is that in many ways the Spaghetti Western functions like an old world opera, instead of a pulp fiction magazine.

Sergio Leone, the quintessential pioneer of the Spaghetti Western drew inspiration from the structure of an opera:

Exposition:

In opera, the overture introduces basic musical themes, establishes the mood, and sets the stage. In Leone’s films, the opening sequences do the same. Only putting it visually, as we are existing within a visual medium.

Like the opening of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: long, silent shots of the desert, accompanied by haunting music and close-ups. There is no dialogue for nearly ten minutes. This works not as narrative exposition. But rather, more like emotional orientation. Leone opens with silence, and tension, not explicit plot. Like an overture, it prepares us for the story come.

Many operas open with an overture full of motifs that reappear during climactic arias. Similarly, Spaghetti Composer’s musical cues plant emotional seeds from the first frame.

Emotional Arias:

An aria is classically defined as a moment when time slows down, plot pauses, and a characters emotion takes center stage. Leone translated this into cinema through stylized, emotionally saturated standoffs, glances, and scenes that linger just a little too long.

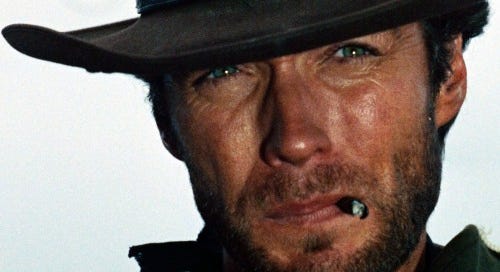

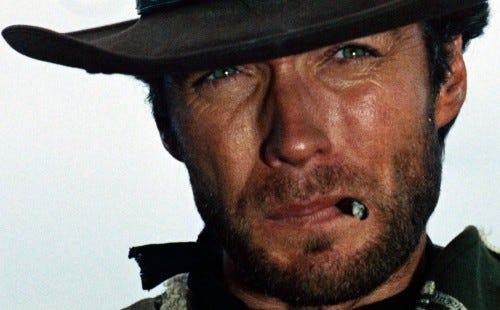

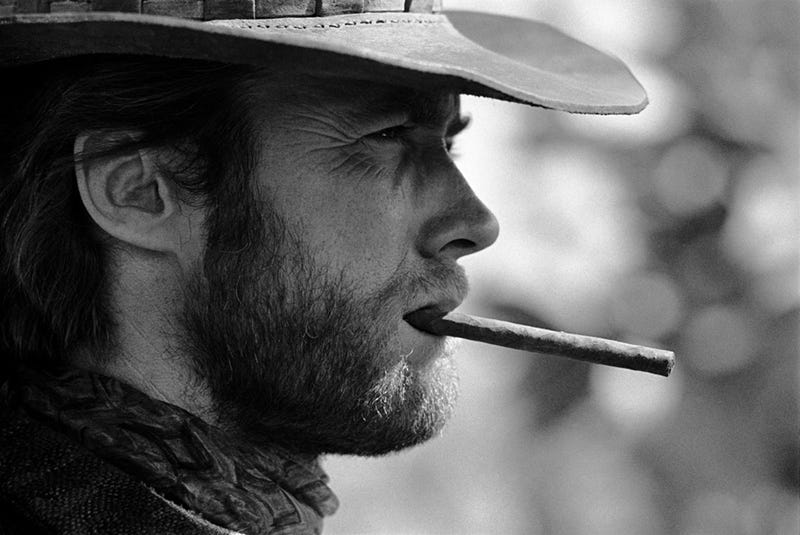

Clint Eastwood’s character lighting a cigar before a duel. A character staring across a graveyard. These moments don’t move the plot forward, but they inflate the emotional stakes.

In Puccini’s Tosca, the aria “Vissi d’arte” is in itself not plot-driven; its Tosca suspended in agony and prayer. Leone’s films have these emotional “suspensions” too, where the story holds still, but the feeling deepens.

Violent Climaxes:

Every opera builds toward a catharsis, and in Spaghetti Westerns, that’s always the shootout. But Leone doesn’t rush there. He stretches these moments like puddy, creating unimaginable tension. The duels often lasted longer than any real-world standoff would. The violence isn’t there for thrill alone; it is the inevitable consequence of the emotions we’ve sat with for two plus hours.

The final scene of Cavalleria Rusticana, a love triangle ends in a fatal duel, and is operatic in form as well as emotion. Leone channels this tradition in his films where vengeance and honor collapse into bloodshed.

Reprise:

The final moments of a Spaghetti Western rarely offer moral clarity or tidy closure. Instead, there’s a reprise of a musical motif, and often a visual return to earlier images.

We’re left with a mood rather than a message. Bitter, yet triumphant, confused, and silent. Leone learned this from opera, where the final bars of music can convey more than the book ever could.

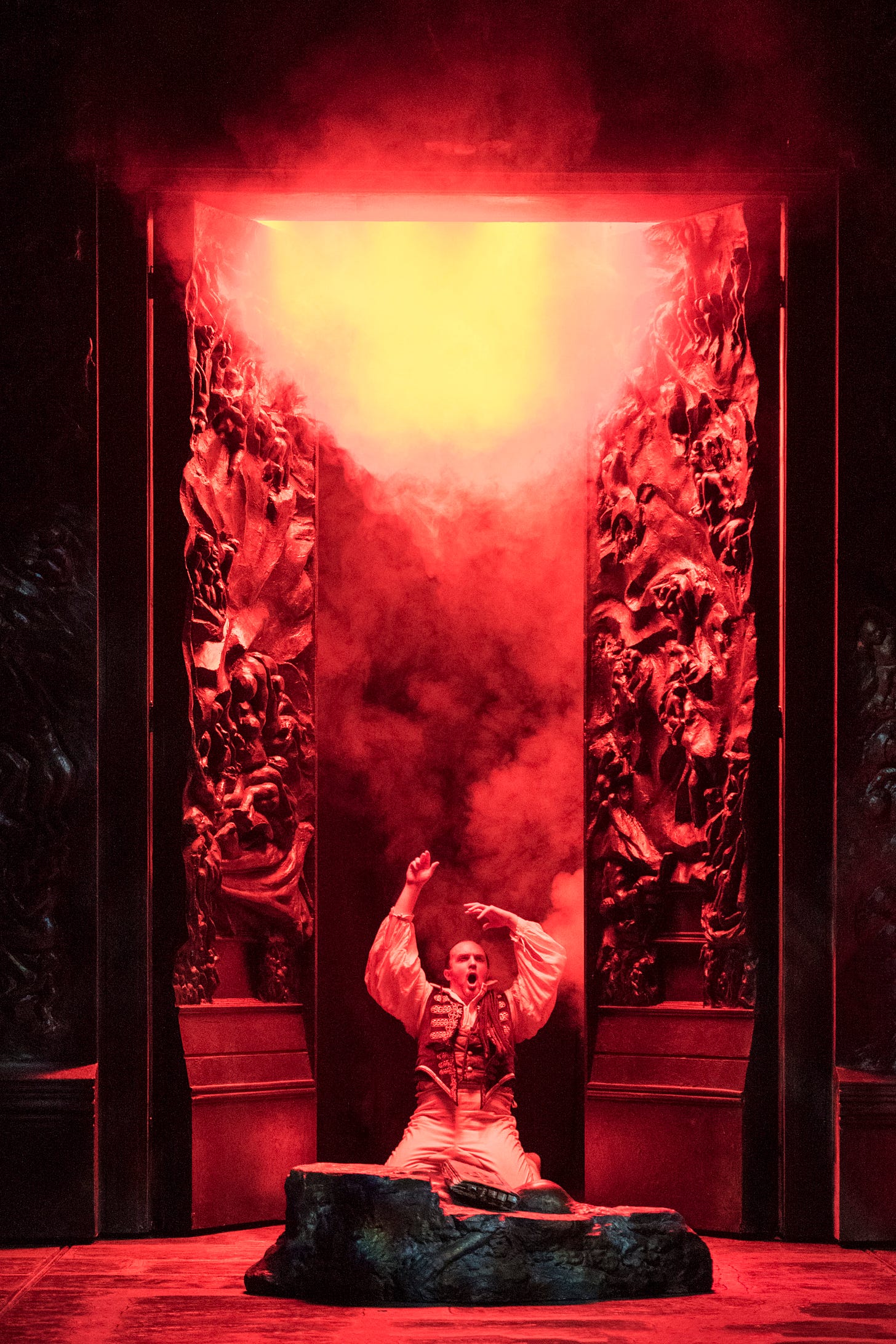

In Don Giovanni, the final scene in which the titular character is surrounded by a chorus of demons who drag him away to Hell (yes actually!!) is undercut by music that leaves the audience unnerved. Similarly, Leone lets the score end the film.

Of course the most important thing in an opera is its music, and a film score holds similar weight. And Sergio Leone's long time collaborator Ennio Morricone redefined film scores with operatic crescendos, vocalizations, unconventional instruments (whistles, ocarinas, harmonicas, etc), turning soundtracks into operatic leitmotifs.

One iconic example is the “coyote howl” motif in The Good, the Bad and the Ugly made using three instruments mirroring Leone’s trio of antiheroes.

Spaghetti Westerns also undermined classic American hero mythology, especially those that had been set up within the genre in the preceding decades in Hollywood. Many of these films “heroes” are mercenaries, villains are ambiguous, violence is loud, fast, and unflinching. Within every one of these three films there are instances of direct brutal, and most shockingly red blooded, violence.

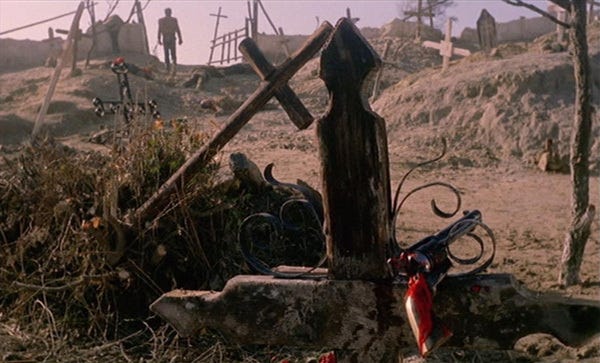

They also often riff on Catholic iconography and existential cruelty, often casting Western landscapes as brooding, and morally unjust spaces. The crucifix makes its first appearance here, and in The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly a major character has an emotional confrontation with his brother, a priest.

These operatic elements don’t appear in theory alone. I found that they erupt through the screen in some of the most defining Spaghetti Westerns ever made.

This week I watched three films that each represent a distinct facet of the subgenre’s evolution:

Django (1966), a down-and-dirty pulp bloodbath that reinvented the genre's grit.

A Fistfull of Dollars (1964), a transitional work that sharpened Leone’s style and deepened his themes.

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966), perhaps the ultimate Western-as-opera. Grand, and grotesque, but huge in scale.

Let’s ride through each, and see how these themes take root in the films themselves.

Act I: Django

A name many casual moviegoers may recognize, a character that was later reintroduced to audiences in 2012 with Django Unchained by Quentin Tarantino. But beyond being reimagined through a more reflective contemporary lens by one of the most prolific directors of all time, Django has his own powerful history behind him.

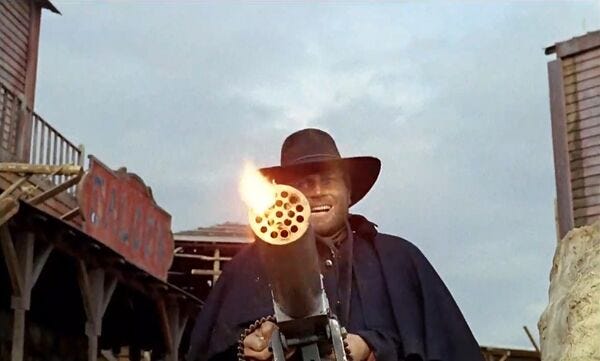

This movie has many iconic moments that have been knocked off countless times, perhaps the most famous though is the titular character rising up from behind a knocked over tree and shooting down 20 some Ku Klux Klan members with a machine gun.

Though not directly recreating this scene could be what inspired the ending of one of the highest grossing films this year: Sinners.

This film also has many of the staples of what connect a Spaghetti Western and a classic European Opera:

The opening visual sets the tone, as if being an overture. Django dragging the coffin across a barren, sun soaked landscape immediately sets a mood of decay and doom. Setting the emotional resonance through imagery, and not yet plot.

Franco Nero, in his breakout role plays a mostly tragic figure: stoic but wounded, vengeful yet his blindly blue eyes are dead. His silence functions like a baritone would in the theatre or the opera. Showing a withheld masculinity.

I have come to understand that in a traditional opera, an aria works while the singer halts the show’s momentum to dwell in a single emotional state. Whether that be grief, vengeance, or longing. In Django, the violence functions in much the same way.

When the Red Shirts massacre the Mexican villagers, it’s almost a visual cry of political oppression. The film forces the viewer to sit in the emotional aftermath.

Similarly when Django’s hands are crushed under the horses’ hooves, it’s an almost biblical passion. His hands are his weapons, his identity, and the moment is treated as such.

The film’s violence is never isolated, it's embedded into the landscape of moral rot.

The setting is a borderland hellhole, stuck between Civil War fallout and revolution, a town with no law, no morality, and no future. Opera often plays out grand political stories through deeply emotional, personal suffering. That’s what Django does.

The film expresses what the characters don't say aloud. Their rage, trauma. It’s theatrical, and it's excessive, but essential.

The graveyard finale, the imagery of hands nailed and broken, and Django’s limp, all show similarities to classic crucifixion/resurrection stories.

Act 2: A Fistfull of Dollars

This movie, unlike Django's visual overture, has literal music underscoring its opening moments set against minimalist visuals, which seem to announce that this is not a typical American Western.

The town in Fistfull is a world in stasis, caught between two feuding families: the Baxters and the Rojos. Similar to Django there is no law, no peace, no morality.

In this town the power is passed like an aria: first to one family, then to the other, then back again, until everyone’s throat is metaphorically (and also literally!) slit.

The Man with No Name archetype enters not as a sheriff or a soldier, but like a trickster god. He is a wandering, masked force who inserts himself into the balance of power and throws the whole system into chaos.

His manipulation of the families mimics the emotional duplicità (duplicity; or deceitfulness) of operatic heroes, he lies, he seduces, and he betrays in service of a large scale reckoning he knows will come.

Act 3: The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly

There are three main characters in Sergio Leone’s masterpiece, each with distinct “voices” (Blondie, Tuco, Angel Eyes) form a dramatic trio, that each represent a moral scale (good, bad, ugly), none of them fully virtuous.

The first 10 minutes are almost silent but fully scored, Morricone’s theme is built on three musical “calls” (coyote howl, flute, ocarina), representing the three characters. Again showcasing the importance of music beyond typical opera or theatre, and how in many cases the music sets up the film in ways the dialogue simply cannot.

As previously touched upon when Tuco (“Ugly”) confronts his priest brother, we’re given a surprising emotional beat for a character that has until this moment been very one dimensional, and played off like a joke. We see his confession, shame, familial pain. It’s the most nakedly vulnerable moment and it comes completely out of left field after a sequence of comedic mishaps, near smack dab in the middle of the film.

The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly also has some of the most striking Catholic, and existential iconography I’ve personally ever seen in film. Crosses, nooses, graveyards, the landscape is reinvented as moral purgatory.

Blondie rides off into the horizon, like many classic Westerns, but the tone is elegiac, not triumphant. Mirroring the beginning, the music concludes the story.

Curtain Call:

The American Western told us stories of how the West was won.

The Spaghetti Western shows us how it was lost.

These films don’t believe in heroes. Here we find that what matters isn’t whether the man with the gun is good or bad.

In A Fistfull of Dollars, Django, and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, violence isn’t chaotic. It’s specific, and its intentional.

To watch a Spaghetti Western is to see power performed, not possessed. These aren’t tales of justice, but of balance. That’s why they resonate even now, perhaps more widely than more traditional Westerns. They show us not a clean-cut past, but a haunted mirror of the present: where war is absurd, power is empty, and violence is always just waiting.

They are operas, not because they’re musical, but also because they are mythic.

Because they understand that in a lawless world, the only order left is rhythm, repetition, and the spectacle of the fall.

The curtain never really comes down in a Spaghetti Western.

Next week we take a look at the frontier itself. The big beauty herself. The muse of every Western every created. We’ll explore how landscapes aren’t just backdrops, but characters in their own right, this is the story of how the West looked… and why it mattered.