Golden Age Gunslingers: Hollywood's Classic Western Boom

Last week (or rather, just moments ago) we explored the roots of the Western genre. We looked at three of the most foundational films in shaping its earliest form, when cowboy stories were still feeling out the edges of their silhouettes.

But those early films, even the most celebrated among them, were just the roots of a much larger tree. A tree that would stretch across decades, twist through American history, and sprout new limbs with each reinvention.

The three films we’re about to discuss come from a moment when the Western really truly arrived, for the first time. This is the point where the genre broke out of its B-movie constraints and galloped into the frontlines of Hollywood, staking its claim as not just popular entertainment, but legitimate art.

Each of these films helped to elevate the Western into something richer, stranger, and more emotionally charged.

They mark the moment when the Western genre stopped looking back. And started looking inward.

We have, in all honesty, skipped over a couple years, and really a whole era of the genre. However many Westerns existed as a secondary genre, focused towards much younger audiences, that in another moment of honesty, are widely accepted to hold no merit.

In the context of this project we are focusing on the movies that made it big. That shot their way through the dust and the noise and laid their stake on Hollywood.

This isn’t the whole story, but these three films show us how the genre found its prestige, popularity, and purpose.

*~*~*~*

I think there is an important side bar that we can take here, so that we can define a word and concept that I and many other filmmakers, historians, students etc will use a lot.

Trope.

I’m sure that most of you have heard the word and most of you also have a pretty solid understanding of what it means. But I have been using the definition that “tropes are stereotypes of film, that often hold dramatic meaning below surface level” in my work and it is a good jumping off point for everyone to understand from now on.

*~*~*~*

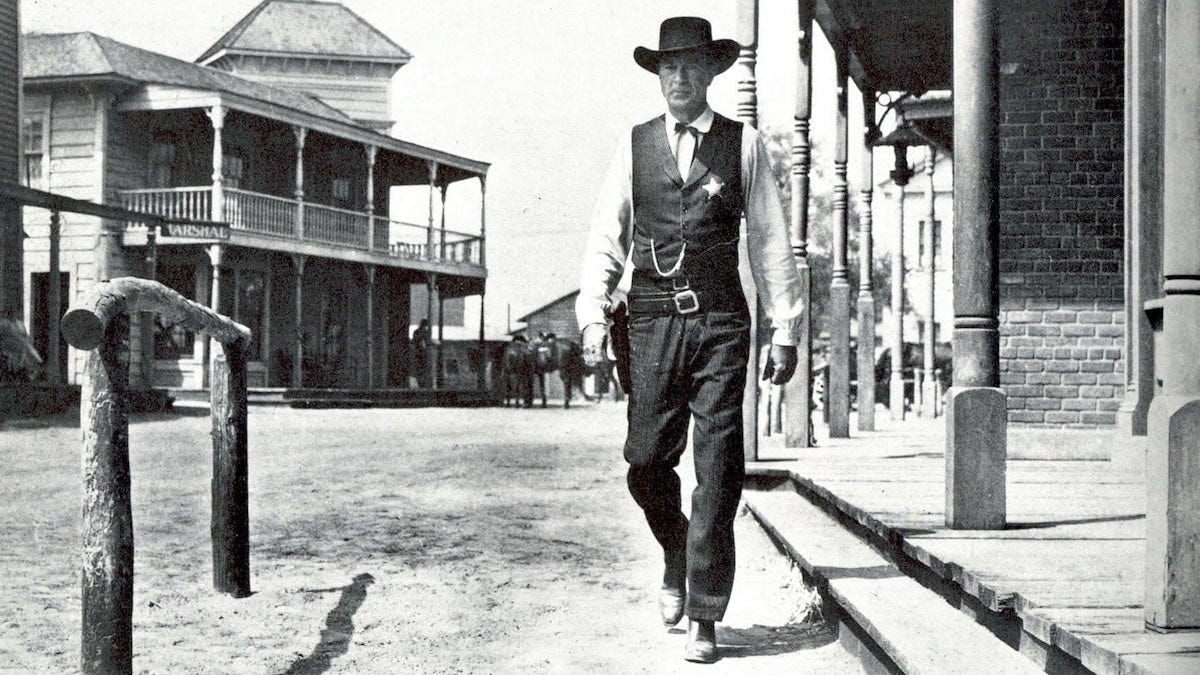

My Darling Clementine (1946) is John Ford’s loosely based take on the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral. A real 1881 shootout in Tombstone, Arizona, between the Earp brothers and the Clanton gang. In Ford’s hands, the event becomes more than historical dramatization. In a way it becomes myth.

This is not just a story of brotherly revenge, but a take on morality, violence, and the fragile bonds between men.

Ford claimed to have spoken with Wyatt Earp himself before the lawman’s death, giving the film a supposed air of authenticity, even though the story is heavily fictionalized.

Released just after World War II, Clementine offered something American audiences were craving: a sense of moral order, heroism, and quiet grace. And yet, Ford elevates the material beyond good-versus-evil simplicity. His West is dusty, slow, and mournful

Ford, already famous for Stagecoach (1939), begins using real people, real events, real locations, but spinning it away from history and making the Western into a form of American Mythology.

Clementine plays with many classic tropes from older Westerns and reshapes them and uses them to show themes of manhood, heroism, and romance.

Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday serve as opposites of each other. Wyatt is a restrained, dutiful hero. Doc is a brilliant, broken soul. A gambler and alcoholic with a knack for reciting Shakespeare.

Even the women in the film symbolize competing visions of the West. In one memorable shot, two women are framed in contrast: Clementine, with her proper dress and gloves, and Chihuahua, a Mexican American singer in a looser, freer outfit, playing slowly strumming her guitar.

These two women create similar opposites as Wyatt and Doc, with Chihuahua, a Mexican American singer representing the Old West. And the titular Clementine represents the New West as she comes in and shows the men in different towns that there is still light in the world to the uncivilized rest of the town that like to create violence and don’t understand Shakespeare.

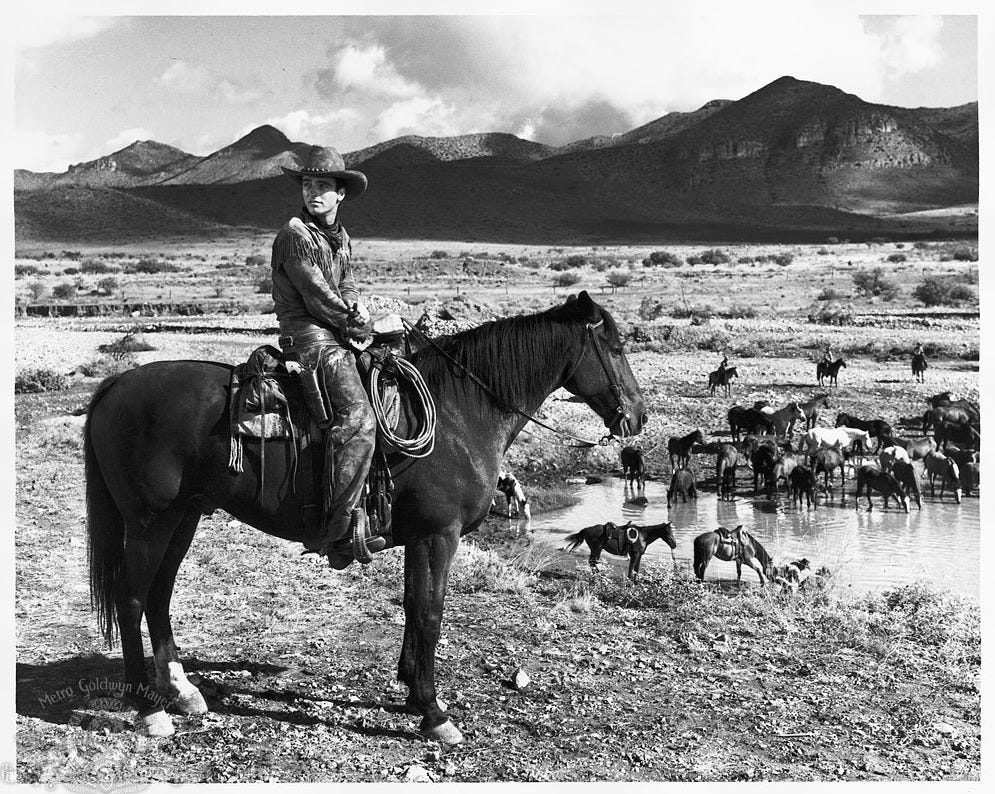

Similarly in Red River (1948) focuses on a dispute between two men in a fictionalized take on real events. This time focusing on the real-life cattle drives across the country. Made as America was moving into its Cold War period and focuses on similar themes of power and manhood, but this time we shift toward generational conflict.

Red River is one of the first true Western epics. Part Shakespearean drama in nature, with a spiraling cast and overlapping blurry motives, part historical cattle-drive saga. And here the Western becomes a canvas for inner turmoil, proving that despite being a genre film it can hold as much emotional weight as a prestige drama.

Montgomery Clift’s performance as Matthew Garth brought a new kind of masculinity to the screen. He was sensitive, modern, and psychological rather than rugged and tough, that would continue becoming more popular in Hollywood, leading to actors like James Dean to emerge.

This film also marked a major turn toward moral ambiguity, in its story, and also in its casting. By the late 1940s, John Wayne was firmly established as the archetypal Western hero. Audiences were used to siding with him by instinct. But in Red River for perhaps the first time, viewers found themselves rooting against Wayne’s character, even fearing him. He’s still a figure of strength and command, but he’s also rigid, obsessive, and at times tyrannical.

In this way River shares similar themes with Clementine, with the Old West authoritarianism vs. New West emotional intelligence.

The final film of this week was made in 1952 and actually stands as an allegory for Hollywood’s moral cowardice during the Red Scare. High Noon can be seen as the story of a lone marshal abandoned by his town feels like a pointed critique of the film industry's complicity and silence in the face of political persecution.

Screenwriter Carl Foreman was himself blacklisted shortly after the film's release.

Marshal Will Kane stands as a stand-in for those in Hollywood who tried to speak up against injustice, only to find that their colleagues, friends, and institutions refused to stand with them. As he walks through town pleading for help, and door after door shuts in his face, the message is clear: silence and self-preservation are the greatest threats to justice. The film doesn’t just dramatize personal courage, it indicates collective fear.

Shot in a minimalist, near-real-time structure, while replacing the Western Frontier with the maze of a small town makes this film claustrophobic and bleak. The hero is alone, old, afraid.

There is no big final shootout, instead there is just a moment of awkward, near silent violence.

High Noon won 4 Oscars including Best Actor for Cooper, as Marshal Kane, a near Christlike figure abandoned by his very own town. This showed the Academy and the public that Westerns could speak to real-world politics and conscience, and could play outside the nostalgic box it had lived in for so long.

And “Do Not Forsake Me, Oh My Darlin’” was one of the first narrative theme songs, which is something that becomes a Hallmark in Westerns in years to come.

These three films each mark a turning point for the Western genre, and for American cinema as a whole. Each one in its own way pushed the cowboy out of the shadows of pulp fiction and into the full light of artistic and emotional complexity. Together, they redefined what a Western could be: not just stories about men on horses, but about power, morality, change, and fear.

This moment in the genre’s history is where we see the cowboy shed his skin. The gunman becomes a poet, the outlaw becomes a metaphor, and the frontier becomes a mirror, reflecting less on the American past, but shifting towards the American psyche.

They each opened the gate for what was to come. A genre that could be political. A genre that could be self-critical. A genre that could evolve.

Next time, we are really going to dive into one of the most interesting parts of this genre, Myth-Making. Which is something that we have begun talking about but is integral to the story and history of Westerns. We are going to focus on two films that tell the story of the same person, and learn how the Myth shifts across time, space, and evolution of the genre.

![My Darling Clementine – [FILMGRAB] My Darling Clementine – [FILMGRAB]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!--89!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fe48c88d4-e25e-4322-87c0-d259b4ee18b0_960x720.jpeg)